Syrian secularists, and moreover the concept of secularism, are under attack online and on the ground. Joseph Daher takes a critical look at recent efforts to discredit the contribution of Syrian secularists to the 2011 revolution and offers historic perspective on the meaning of secularism and how the concept has been used and misused in the battle to shape the future of Syria. The first part of this article examines the role of secularists and secularism in the Syrian uprising, how secularism is defined and whether the Assad regime historically helped or hindered secularist forces in Syria.

Author Joseph Daher

In the opposition website Zaman al-Wasl, the author Hilal Abd al-Aziz al-SFa’ouri launched a new attack on secularists with an article entitled ‘What Syrian secularists want from the Syrian Muslims.’ In it, he describes all secularists as critical of “everything that belongs to Islam”, and claims they hold a “secret hostility towards Muslims” by notably wanting them “to shave their beards and take off their jilbabs [traditional Arabic garb] and throw their turbans… to close their mosques and not pray.” Fa’ouri is the author of numerous articles on opposition website Zaman al-Wasl.

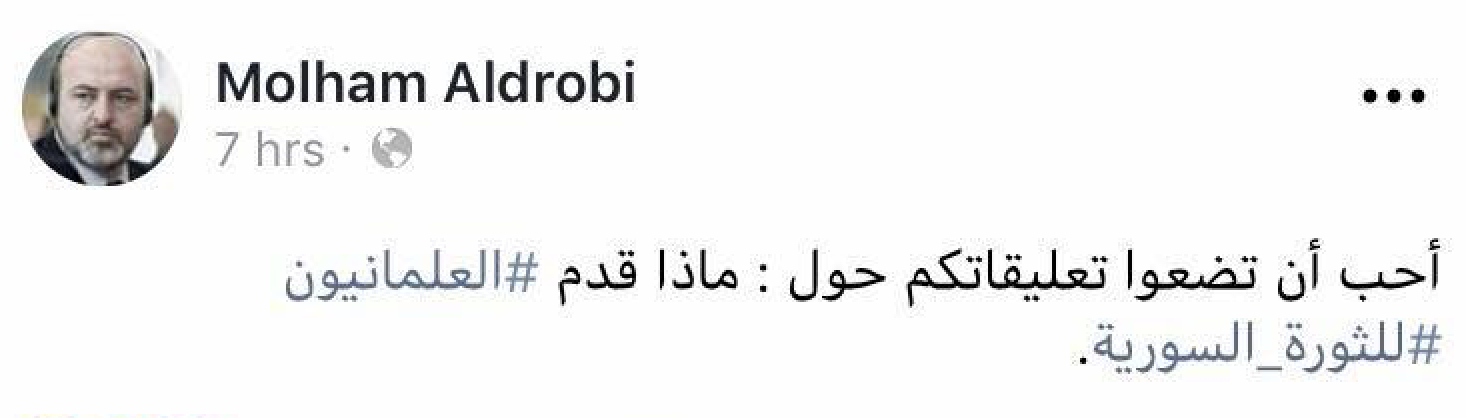

It is probably no coincidence this article comes just a few weeks after one of the leaders of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood, Molham al-Droubi, posted on his Facebook profile the following request: “I would like to have your comments on: what did the secularists offer the Syrian revolution”, as a clear provocation towards these sectors of the opposition. His comment led many secular activists to answer him either directly or indirectly on social networks. Previously, other Islamic fundamentalist and jihadist groups and personalities had attacked secularists as “foreign tools,” rejecting their role in the uprising and the concept of secularism as a heresy or apostasy. These attacks on secularists and secularism raise several questions and issues that need to be tackled.

What secularists offered the Syrian revolution

First, the issue of the participation of secular activists in the 2011 uprising shouldn’t even be up for debate. Secular activists have been actively involved in various phases of the struggle against the ruling regime, both before and after the unrest of 2011. Numerous secular activists played an important role within the grassroots committees and in the development of peaceful actions against the regime. These gatherings slowly developed internal structures and several coordination committees played a particularly important role fostering solidarity links on a national level, particularly the Syrian Revolution Coordinators Union (SRCU), Union of Free Syrian Students and the Local Coordination Committees (LCC) and many other youth groups such as the Syrian Revolutionary Youth. The Syrian grassroots civilian opposition was indeed the primary engine of the popular uprising against the Assad regime for the first two years. The repression, militarization, rise of Islamic fundamentalist and jihadist forces, coupled with foreign interventions changed this situation. Syria’s uprising transitioned from a popular revolution into an international war.

Secularism is not the opposite of faith or a demand for the eradication of religion from society. One can be a believer and at the same time support secularism as the organizing principle of the state and society.

Second, the recent negative attention directed at secularists on social media and Syrian opposition outlets fits into wider regional and historical patterns. Most of the conservative and Islamic fundamentalist forces in the Middle East have spent decades negatively describing secularism as a form of heresy, apostasy, atheism and an attack on Islam, a product of the west and therefore as a concept to be combatted. The Egyptian Salafist Sheikh Youssef Qaradawi, an influential cleric residing in Qatar and who is linked to the MB stated the following in one of his numerous books attacking the concept of secularism:

“Secularism may be accepted in a Christian society but it can never enjoy a general acceptance in an Islamic society… For Muslim societies, the acceptance of secularism means something totally different. Since Islam is a comprehensive system of` Ibadah (worship) and Sharia (legislation), the acceptance of secularism means abandonment of Sharia, a denial of the Divine guidance and a rejection of Allah’s injunctions. It is a total falsification to claim that Sharia is not proper to the requirements of the present age… For this reason, the call for secularism among Muslims is atheism and a rejection of Islam. Its acceptance as a basis for rule in place of Sharia is a downright apostasy.” [i]

These remarks were made in his book ““How the Imported Solutions Disastrously Affected Our Muslim Nation”. The cleric spreads similar views as a weekly guest on Al-Jazeera where he has his own program.

Cartoon depicting the struggle between political Islam and authoritarianism (© SyriaUntold)

Cartoon depicting the struggle between political Islam and authoritarianism (© SyriaUntold)In Syria, democratic, secular and liberal thinkers and groups have endured verbal and physical attacks from Islamic-leaning movements because of their ideology since the start of the uprising in 2011. The most recent display of anti-secularist sentiment came with the military invasion of Afrin and its subsequent occupation by the Turkish army and Syria armed groups affiliated to Ankara, mostly conservative and Islamic fundamentalists. Some of the Syrian fighters participating in the offensive and the subsequent occupation of Afrin attacked the Kurdish Peoples’ Protection Units (YPG) not solely because of their ethnic origins or on the basis of “accusations of siding with the regime”, but also because their political party promotes a particular brand of secularism. Its historic roots are close to Marxism and Third worldism[ii][ii] but the group’s ideology has evolved beyond that, reflecting the influence of American social theorist Murray Bookchin, a thinker advocating “libertarian municipalism”. The main incentive for the Turkish led military operation of Afrin was to prevent the YPG from controlling contiguous territory along its border, as it considered its political branch, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), as a terrorist group linked to its own Kurdish insurgency, spearheaded by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The offensive in Afrin fits into a much larger war pitting Ankara against the PKK. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has reiterated on numerous occasions that its armed forces would press their offensive against Kurdish YPG fighters along the length of Turkey’s border with Syria and if necessary into northern Iraq.

Defining secularism

In Syria, democratic, secular and liberal thinkers and groups have endured verbal and physical attacks from Islamic-leaning movements because of their ideology since the start of the uprising in 2011.

It is essential to define what we understand by secularism and a secular state. At a minimum, the concept encompasses the separation of the state and religion; and the neutrality of the state towards believers and non-believers, including in the distribution of a resource or opportunity. Religion and religious institutions do not rule or impose its laws on society, while no religious creed is privileged over another. At the same time, freedom of conscience guarantees the right of believers to practice their religions and of non-believers to not believe or practice any religious dogma.

The concept of secularism has taken different paths according to the history of each society. [iii] In the Middle East, the first modern contemporary debates around the concept of secularism began in the mid 19th century led by intellectuals of the region, during the period called the “Nahda” (Renaissance), accompanied by other related discussions in regards to the challenges of the time, most notably on how to challenge western domination and colonialism. In the 20th century, and the rise of Arab nationalist and communist movements in the region, the idea became more widespread. Conservative and Islamic religious forces, aided by Saudi Arabia and Western powers at the time, increasingly responded to these rising forces by categorizing them as foreign ideologies attacking Islam and as equivalent of atheism seeking to erase religion of society. Secularism is still presented today by many Islamic fundamentalist movements in this way. This is of course not limited to the Middle East.[iv]The rise of religious fundamentalism is indeed an international phenomenon, not something unique to the Middle East or other societies with predominantly Muslim populations. We have seen the development of similar political currents like Christian fundamentalism, Hindu fundamentalism, and Jewish fundamentalism in Israel, that all have their own peculiar brand of right-wing politics. But none of them, despite their call to return to an earlier golden age, should be seen as fossilized elements from the past. They may employ symbols and narratives from earlier periods, but all these fundamentalisms are the product of modern societies.[v]

Syria under Assad, secular?

Syria may be religiously and ethnically diverse but the state is not secular in character. The regime of Bashar al-Assad has been no exception. The 2012 constitution stipulates that the president must be a Muslim man or that “the main source of law is the Sharia”. Syria also has eight different personal status laws, each of which is applied according to the religious sect of an individual[vi]. These laws also include major discriminations against women. In 2010, several Islamic clerics such as Sheikh Osama Rifai, who is now in exile for his opposition to the regime and has established the Syrian Islamic Council, and Sheikh Ratib al-Nabulsi, who has not opposed the regime, portrayed the The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) “as a grave threat to the lives, morals, and religious values of Syrians”, while supporting the several reservations made by the regime affecting key provisions of the covenant against the opposition of feminist movements. For example, reservations were made against Article 2 of the CEDAW, which mandates notably the States parties enshrine the principle of equality between men and women in their national constitutions and other appropriate legislation, and to ensure, through law and other appropriate means, including sanctions where appropriate, to prohibit all discriminations against women.[vii]

Banner raised in one of the demonstrations in the city of Aleppo. Image taken from social media and published here under fair use.

Banner raised in one of the demonstrations in the city of Aleppo. Image taken from social media and published here under fair use.Historically, the Assad regime since the period of Hafez al-Assad has developed a religiously conservative discourse and encouraged a conservative Islamic establishment to channel Islamic currents and legitimize the regime. They also started to sponsor and institutionalize alternative Islamic groups that were willing to play along with its political game such as the Naqshbandi Kuftariya Sufi order under Sheikh Ahmad Kuftaro and groups affiliated with Sheikh Sa’id al-Buti’s or the Qubaysiyyat female Islamic movement.[viii] These policies and rapprochement with religious conservative layers of society coincided with censorship of literary and artistic works, while promoting religious literature that filled the shelves of libraries and Islamizing the field of higher education.[ix]Feminist activists and groups were publicly accused by religious conservative movements close to the regime of heresy and of seeking to destroy society’s morality, of propagating Western values, such as the notion of civil marriage, the rights of homosexuals and lesbians, and total sexual freedom.[x] This is without forgetting the long history of relations of the Assad regime with Islamic fundamentalists groups in Syria and outside, as well as its instrumentalization of jihadists groups at different times, including during the U.S.-led occupation of Iraq.

Secularism, extremism and the survival of the Assad regime

Similarly, there was a clear strategy by the Assad regime since the beginning of the uprising to favor and allow the creation of Islamic fundamentalist and Salafists jihadists’ organizations to discredit the popular movement and its initial inclusive message. This was evident in the decision to release numerous jihadist and salafists from its jails after the start of the protest movement, while repressing democratic and progressive components of the civilian opposition as well as the Free Syrian Army. In tandem to these developments, protesters established alternative institutions such as the local coordination committees and councils, which challenged and replaced the state by providing services to the local population in areas where state was no longer dominant. By developing these institutions, the protest movement provided a political alternative that could appeal to large sections of the population, especially in its first six months of demonstrations and before the large-scale militarization of the uprising.

The challenge became greater for democratic and progressive components of the protest movement as a result of the evolution and dynamics of the uprising. The inclusive and democratic message of the initial protest movement, as well as its vitality, was weakened considerably firstly by the regime’s repression and war against democratic components of the protest movement, while the subsequent rise of Islamic fundamentalist and jihadist movements weakened these sectors even further.

This created a double advantage for the regime. Firstly, it presented itself as a bulwark against “extremism” internationally and therefore trying to include its murderous war on the Syrian population in the so called “war on terror” led by Western states and authoritarian regimes in the region and throughout the globe. Secondly, it allowed it to play on the fear among sections of the population who rightly viewed these forces as an existential threat. Jihadist and salafist actors, which were subsequently supported by Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey, promoted a vision of society that was of course an exclusionary project and was not appealing to various groups within Syrian society such as religious minorities, women, or those who had a different understanding of Islam. The regime promoted itself on its side as “the protector of minorities” and of “modernity”, although this as mentioned earlier was very far from the truth. In this context, each defeat of the democratic strands within the protest movement, both civilian and armed, strengthened and benefited Islamic fundamentalist forces. Progressively, these elements dominated the military scene.

(© SyriaUntold)

(© SyriaUntold)Secularisms and undemocratic secularism

Does this mean that secular political systems are necessarily good? No not at all, for example on an international level, the French state is very far from being a model to follow and rather should be condemned for its instrumentalization of secularism to implement discriminatory and racist laws against Muslim people, especially women by forbidding for instance the wearing of the veil in public schools. The issue of whether or not to wear the veil concerns only women, and they must make that decision independently and by themselves. Imposing or withdrawing the wearing of the veil by force is a reactionary and anti-democratic act, which goes against any support for women’s self-determination.

More generally the rise of Islamophobia,[xi] particularly in Western countries must be denounced, as any other forms of racisms.

Secularism is not the opposite of faith or a demand for the eradication of religion from society. One can be a believer and at the same time support secularism as the organizing principle of the state and society. Already Abdel Rahman al-Kawakibi, a Syrian Islamic reformist thinker and important figure of the Nahda, at the end of the 19th century, for instance stated in the chapter on despotism and religion in Tabd’i al-istibdad, that a “distinction must be made between religion and state, because this distinction is now a major requirement of the time and place in which we live”.[xii]

Similarly Ali Abdel Razeq, in his 1925 book ‘Islam and the Foundations of Governance’ (Al-Islam Wa Usul Al-Hukm) argued mainly that Islam did not advocate a specific form of government” and against a role for religion in politics or the political prescriptive value of religious texts.

More so, secularism gives the believers the possibility of liberating themselves from the instrumentalization of religion by state and political parties and enables them to practice their religion freely without state oppression.

What about secularists, do they form one single group? No. Quite the opposite. In Syria we find secularists among supporters of the regime and in the opposition. Differences also exist within these groups. In the opposition for example, secularists have not constituted a single pole and this is quite normal as different political tendencies exist from leftists and feminists to liberals, nationalists and conservative groups. While they may have some common points on the concept of secularism, despite deep differences, they do not share the same political program regarding many various issues such as what kind of economy, women’s rights, the Kurdish issue, imperialism, etc… This tendency to politically homogenize secularists in one single group undermines the concept of secularism more generally.[xiii]

Article first published on the website Syria Untold: http://syriauntold.com/2018/08/secularists-secularism-and-the-syrian-uprising-part-1-2/#post-settings-55400

[i] https://ia802305.us.archive.org/2/items/FP0203/0203.pdf, p. 67

[ii] View: https://wordpress.com/posts/syriafreedomforever.wordpress.com

[iii] For example, Karl Marx rejected as idealist the notion that the main task of revolutionaries is to attack religion such as promoted by many intellectuals of the Enlightement period in Europe. Marx argued that there is a real material basis for religious belief – the terrible conditions in which the mass of oppressed humanity are forced to live. Only with the elimination of those oppressive material conditions will religion fade away. Karl Marx also opposed atheism being inscribed as part of the political program of the revolutionary movement.

[iv] See https://www.opendemocracy.net/rajeev-bhargava/states-religious-diversity-and-crisis-of-secularism-0#_edn1

[v] See Martin E. Marty, ‘Fundamentalism as a Social Phenomenon,’ Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 42, no. 2 (1988)

[vi] Christian communities follow their own laws, while Personal Status Law for all Muslims is based on a particular Sunni interpretation of Islamic Sharia, Hanafi jurisprudence and other Islamic sources.

[vii] See Kannout, Lama (2016), ‘In the Core or on the Margin: Syrian Women’s Political Participation,’ UK and Sweeden, Syrian Feminist Lobby and Euromed Feminist Initiative EFI-IFE

[viii] At the same time, the Assad regime repressed, particularly in the end of the 1970s and beginning of the 1980s, Islamic fundamentalist movements, such as the Muslim Brotherhoods, opposing it. See Khatib Line (2011), ‘Islamic Revivalism in Syria, The rise and fall of Ba’thist secularism’, London and New York, Routledge Studies in Political Islam; Pierret, Thomas (2011), ‘Baas et Islam en Syrie’, Paris, PUF; Imady, Omar, (2016) ‘Organisationally Secular: Damascene Islamist Movements and the Syrian Uprising’ Syria Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1, pdf. Pp.66-91; Lefèvre, Raphael (2013a), ‘The Ashes of Hama, the Muslim Brotherhoods in Syria’, London: Hurst

[ix] Pierret, Thomas (2011), ‘Baas et Islam en Syrie’, Paris, PUF, p. 115

[x] Aous (al-), Yahya (2013), “Chapter 3: Feminist Websites and Civil Society Experience”,in Kawakibi S. (ed.) Syrian Voices From Pre-Revolution Syria : Civil Society Against all Odds, HIVOS and Knowledge Programme Civil Society in West Asia. (pdf.). Available at: https://hivos.org/sites/default/files/publications/special20bulletin202-salam20kawakibi20_6-5-13_1.pdf, (accessed 3 March 2014), p. 25

[xi] Islamophobia is understood as by the author a form of religious bigotry mixed with racism directed against the Muslim population.

[xii] As noted by librarian and scholar George N. Atiyeh « Whether al-Kawakibi’s secularism was complete or not is a debatable question in more than one way. His introduction of the idea of spiritual caliphate led him necessarily to consider politics as an autonomous discipline, a position which placed him almost alone among the modern reformers of Islam”… such as for example Rashid Rida, the counter-reformist per excellence and , pointed out his disapproval of al-Kawakibi’s concept of the separation of state and religion. http://www.syriawide.com/atiyeh.html

Rida transformed the reformist tendencies of pan-Islamism, particularly of famous reformist intellectuals such as Mohammad Abduh and Jamal al-Din Afghani, toward a fundamentalist orientation. Rida’s evolution brought him closer to the puritan Hanbali doctrine, particularly its Wahhabi followers. He became a determined defender of the Saudi regime and Wahhabism, while collaborating with Saudi King Abdel Aziz. He started opposing and fighting the Sufi brotherhoods and practices of their adherents. He argued for the restoration of the caliphate after its abolition in 1924. He also developed a strong anti-Shia diatribe, accusing Arab Shia of being agents of Iran (a theme often found today among Salafis and other Islamic fundamentalist movements). Rashid Rida particularly had a prominent influence on the intellectual and political framework by the Muslim Brotherhood as he sought to revive Ibn Tammiyya’s literalism and call for jihad. This new Salafi tradition was spread individually by intellectuals like Rashid Rida in the 20s and 30s, and socially by groups such as the Brotherhood later in Egypt and elsewhere

[xiii] It is important also to note that similarly that all political movement rooted in religion should be treated homogenously. As the Syrian writer Aziz Al-Azmeh, stated that “the understanding of Islamic political phenomena requires the normal equipment of the social and human sciences, not their denial” Not acting in this ways, will lead us to an essentialisation of “the Other”, in much of the current cases today of the “Muslim”. Each religion does not exist indeed autonomously of people, in the same way that God does not exist outside of the field of intellectual action of man. This is why we must reject Islamophobic claims that the roots of ISIS, al-Qaeda, Boko Haram, and other fundamentalists can be found in the Koran. Such groups and their actions should be analyzed as the product of international and local social, economic, and political conditions in the present time, not as the product of a text written 1400 years ago. Do we explain the US invasion of Iraq by the religious beliefs of George Bush (who reported that God told him in a dream to invade Iraq)? Of course not. We instead explain Bush’s war, his motives, and their ideological justification as the product of American imperialism.

At the same time, we have seen in the past movements or individuals rooted in religious identity develop progressive policies. The Christian liberation theology had developed a radical critique of capitalism against the dictatorships of South America, while black Muslim intellectual and activist Malcolm X who, while remaining faithful to his religious beliefs, especially at the end of his life was moving to the left. He did not hesitate to criticize Muslim leaders in an interview in 1965, which he accused of having voluntarily kept the people, and women in particular, in the dark. He added that the state of progress of a society is measured by the situation of women, stating that “the more women are educated and involved … the more the whole people are active, bright and progressive”.